Popular Posts

-

A common statistic that many people have begun to value and notice a lot recently is the chances created statistic. Chances created, accordi...

-

Last year I was planning on going to go to the Sloan Sports Conference but ended up not being able to make it. I was thinking abou...

-

Pretty soon I'm going to start writing the Manchester City statistical blog over at http://www.eplindex.com/ (@EPLIndex). I also...

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Does More Possession=More Wins in the MLS?

In the past couple of blog posts I've looked at two common statistics and shown that they are not as meaningful as most people believe. shots on goal do not predict success very well, and assists favor players on better clubs. In keeping with this theme of misleading statistics in football, I decided to look at possession data. The commonly held notion is that the team that has the ball more (has a possession percent over 50) is more likely to win. This makes sense. A team with the ball more is more likely to score and less likely to concede. But does the data back it up? Does having more possession than your opponent mean you are more likely to win the game? I looked at the possession data from the MLS season so far. What I found goes completely against what most people would think. So far this season in the MLS, the average possession percentage for teams that have won the game is 48.5%. Teams that win actually posses the ball less. This means the average possession percentage for losing teams is 51.5%.

To get even more specific, I broke down the possession data further. Winning home teams average 50.9% possession, and winning away teams average 43.4% possession. On the other side, losing home teams average 56.6% possession and losing away teams average 49.1% possession. The histograms below illustrate these facts. I found that away teams, on average, have a possession percentage of 47.3%, and home teams have a possession percentage of 52.7%.

So what does all this mean? It seems possession percentage in the MLS does not predict success. Teams that possess the ball more don't win more; they actually lose more. Home teams also have a slight advantage in possession percentage compared with away teams.

What about teams that completely dominate possession? You might think that a team that had the ball much more often than their opponent would be much more likely to win. I defined "dominating possession" as having the ball more than 60% of the time. So far this season, teams that have dominated possession have a record of 10 wins, 19 losses, and 18 ties. Domination in possession? Yes. Domination in wins? No.

This analysis calls in to question statements like "the Union had the run of play, they possessed the ball more and deserved the win." It's apparent that in the MLS, possession is not all that important when it comes to winning games. So what's the problem with possession? One reason could be that the best teams do not play possession football. The teams with the most success may play kick and run. Another possibility is that possessing the ball simply doesn't lead to wins. Either way, having the ball more than your opponent does not mean much in the MLS.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Why We Shouldn't Put Much Value in Assists

Last week I wrote a post on why shots on goal are a misleading statistic. In keeping with the analysis of the problems with some commonly kept statistics in football, I decided to look at assists.

If you think about it, assists are highly misleading. Simply playing with good players boosts your assist total. Similar to shots on goal, not all assists are the same. There are the assists where a player makes a short pass in the midfield that leads to a teammate dribbling through all the opposing defenders and finishing, and the assists where a player makes a beautiful cross where their teammate simply has to tap the ball in the open net. These obviously shouldn't be counted as the same value to the team, yet they are. Hell, I could probably record an assist eventually in the EPL if I played for one of the top teams (OK, maybe an exaggeration but you get the point.)

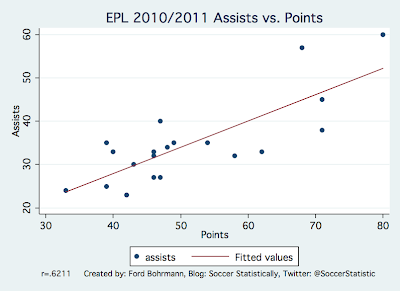

First, let's look at the assists data for all the teams in the EPL league. As the graph below shows, as the point value of a team increases (basically, the better the team is) the assist total also generally increases. This is no surprise. We would expect better teams to score more goals and thus have more assist totals.

Basically what this means is that the assist statistic should favor players on better teams. Players on better teams play with better teammates and should therefore have more opportunities for assists. Below is a screenshot from the EPL website of the players with the top 20 assist totals.

9 players from top 5 clubs are in the top 20 for assist totals. No players from bottom 3 clubs are in the top 20, with the exception of Blackpool's Charlie Adam who was just signed by Liverpool. It's easy to see assists totals are higher for players on better clubs.

A better statistic that is not influenced by the quality of your teammates are chances created. A chance created is defined as a pass that leads to a shot. These are obviously not as dependent on your teammates and give a more fair and true assessment of how much of a playmaker that player is for their team.

The next time a club is looking to sign a player based solely on their assists totals, they should take a more in depth look. Assists can tell an inaccurate, or at the least biased, story.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Do Shots on Goal Matter?

The major point of this blog is to test commonly held notions in football for their validity. After watching the US women lose to Japan yesterday, I started to think about shots on goal. I don't have the exact numbers, but I'm pretty sure the US crushed Japan in the shots on goal category. This made me think, do shots on goal matter? Most people would quickly say yes. It would make sense that more shots on goal mean more chances to score and thus more goals. The only problem is that some things in football just don't make sense. I wanted to see if shots on goals equate to success in two categories: 1.) Do more shots on goal mean more success for a team as a whole? 2.) Do more shots on goal mean more goals for a specific player? To test these questions I used data from the MLS website. As an aside, mls.com has extensive statistics for every season in a bunch of categories. Great to see. Anyways, the data is from the 2010 MLS season.

First question: Do more shots on goal mean more success for a team as a whole?

If this was true, we would expect points to increase as shots on goal increase on a team level. In other words, teams that have more shots on goal would be more successful. The graph below tells us a different story.

Second question: Do more shots on goal mean more goals for a specific player?

Similar story for this question: is there a linear increase in the amount of goals as the amount of shots on goal increases? The graph below gives us the answer.

This graph shows a stronger relationship compared with the graph above. However, the relationship is still not very strong. The value of r in this case is .4722, indicating that the relationship is stronger than the graph above. However, a correlation under .5 is generally considered to be a weak relationship. This means for individual players, shots on goals are not a very good indicator of goals.

Here's my best explanation for why shots on goal are not a very indicative statistic: Not all shots on goal are the same. There are 40 yard weak rollers that the goalie easily saves, and there are 5 yard shots that the keeper barely gets a hand on. There are weak attempts by a center back getting forward and there are breakaways by forwards. In the shots on goal statistic, in both cases the shots on goal are counted as equivalent. Obviously this makes no sense. A statistic that would be better indicative of goals scored for both questions I looked at above would be shots on goal inside the box. Shots on goal inside the box would get rid of the shots on goal that have no chance of going in. Not all shots inside the box are the same, so we have somewhat of the same problem as shots on goal. However, I assume there would be a much stronger correlation between shots on goal inside the 18 and points, and shots on goals inside the 18 and goals by an individual player. Unfortunately, I don't have the data to back up this claim (working on it). If/when I do get the data from shots inside the box I'll post the graph and the correlation between shots on goal in the box and goals.

Even without the data, the point I'm making is still clear: shots on goal do not equate to more success from a team perspective and do not correlate with goals for individual players very strongly like most people assume they do. There are better statistics than shots on goal. This means statements like "New England had 5 more shots on goal than New York, they dominated the game" and "Donovan had 4 shots on goal in the game, he was due for a goal" are not neccesarily valid. What if New England had a bunch of shots on goal from outside the 18 that never had a chance of going in? And what if Donovan's shots on goal all were weak rollers? Shots on goal are often misleading.

Thursday, July 14, 2011

A Different Look at League Parity: MLB vs. EPL

I was intrigued after reading a post last month by Chris Anderson on his Soccer By the Numbers Blog. The post compares the competitiveness of different football leagues in Europe. You can find it here. Anderson talks about "uncertainty of the outcome" as a measure of parity. This makes sense, as leagues where the outcome is not a sure thing are more equal.

With an uncertainty of the outcome in mind, I took another approach to analyzing the parity in a league is by looking at the amount of champions. In the past 10 years, only 3 clubs have won the English Premier League. In baseball, 9 different teams have won the World Series. Of course, this has flaws and is not a complete look at the league. This does suggest that the outcome is not fixed for baseball though.

Does this mean that professional baseball has a more balanced league than the EPL? If you've read Moneyball by Michael Lewis (if you haven't you should) you would know that MLB is facing payroll disparities similar to the one's in the EPL. So why the large difference in the number of winners? The answer is the playoffs.

In baseball, the 6 division winners plus 2 wild cards make the playoffs. There is one best of 5 series, followed by 2 best of 7 series. This adds up to only 11 wins to take home the World Series. Most people say that the playoffs are different than the regular season. They say all previous records are thrown out the window and any team can beat any other team. While there may be some change in the way a team plays when it comes to the playoffs, there is a more important factor at work: a small sample size of games. With such a small sample, it is not uncommon for a less skilled team to simply get lucky and beat a better team. Assume a team has a 30% chance of beating another team in a playoff game. For a best of 5 series, that team has a 16.3% chance of winning. For a best of 7 series, the team has a 12.6% chance of winning. All in all, upsets are not uncommon in the MLB playoffs. These upsets are the force behind the multitude of World Series winning teams this decade.

In contrast, we can look at the EPL. The EPL has no playoff system, and the winner is determined by the most number of points after each team plays 38 games. Effectively, you can look at this as just being one long playoff. Here, the sample size is much bigger: 38 games. Historically, teams have to win above 25 games to win the league (with the exception of last season). If we look at an above average team, what is their chance of winning more than 25 games? Let's take Liverpool from last season. For simplicity's sake I will only look at wins for the analysis. This may hurt a team with a lot of draws, but it makes the analysis a lot simpler. Last season they finished 6th with 17 wins. This means they win about 45% of their games. I am also assuming that Liverpool's record is an accurate measure of their ability to win games. In other words, Liverpool really does have a 45% chance of winning a game. The probability of Liverpool winning more than 25 games last year, if they have a 42% chance of winning each game, is .3%. For a team that won 25 games, or 65% of their games (in the past 10 years it has been ManU, Chelsea or Arsenal), the chance of winning more than 25 games is 42% Because of the bigger sample size, upsets are much less likely in the EPL. Even with a good team like Liverpool (I don't think anyone would say Liverpool winning the league is an upset), the probability of it happening is very low.

Baseball's smaller sample size of games in the playoffs allows for upsets and gives the appearance of parity with numerous teams winning the World Series. The EPL's larger sample size and lack of playoffs vastly reduces the chance of an upset which leads to the same powerhouse teams winning over and over again. John Henry already has two championships this decade with the Red Sox. The way the leagues are set up, a third championship with Red Sox is more likely than his first with Liverpool.

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

WPA and AGW Weekly Updates this Season

I just added the image on the right of the page ranking the players ranked by their WPA totals. The chart also includes the player's AGW and their goal totals for the season. I'll update this every week during the EPL season. An explanation of WPA and AGW are below.

WPA: Win Probability Added defines exactly what it sounds like it should: How much a player has added to their team's success through their goals. The way I calculate this is to sum how much each player's goals add to the team's probability of winning. Goals are a flawed statistic because every goal is obviously not worth the same amount. The 5th goal in the 90th minute in a 5-0 win is not important. The 1st goal in the 90th minute in a 1-0 win obviously is very important. To quantify these values I accumulated the total record (wins, losses, and ties) of every game in the past 10 years in the EPL. This way, I could calculate the exact winning percentage at every different game situation for both teams. For example, I know that scoring the 2nd goal to make a game 2-0 at home in the 67th minute increases a team's chance of winning by 10.845983%. WPA takes in to account the importance of each goal, and shows how much, overall, a player has added to their team's chance of winning a game through their goals.

AGW: Average Goal Weight is simply how much, on average, the player's goal is worth. Mathematically, it is the player's total WPA divided by the number of goals they have scored. For example, one player may only score 5 goals on the season, whereas another may score 15. However, the first player could have a higher AGW if they tended to score pivotal goals while the second player scored useless goals.

WPA and AGW are not perfect statistics, but they do provide a little more insight in to a player's goal scoring ability.

WPA: Win Probability Added defines exactly what it sounds like it should: How much a player has added to their team's success through their goals. The way I calculate this is to sum how much each player's goals add to the team's probability of winning. Goals are a flawed statistic because every goal is obviously not worth the same amount. The 5th goal in the 90th minute in a 5-0 win is not important. The 1st goal in the 90th minute in a 1-0 win obviously is very important. To quantify these values I accumulated the total record (wins, losses, and ties) of every game in the past 10 years in the EPL. This way, I could calculate the exact winning percentage at every different game situation for both teams. For example, I know that scoring the 2nd goal to make a game 2-0 at home in the 67th minute increases a team's chance of winning by 10.845983%. WPA takes in to account the importance of each goal, and shows how much, overall, a player has added to their team's chance of winning a game through their goals.

AGW: Average Goal Weight is simply how much, on average, the player's goal is worth. Mathematically, it is the player's total WPA divided by the number of goals they have scored. For example, one player may only score 5 goals on the season, whereas another may score 15. However, the first player could have a higher AGW if they tended to score pivotal goals while the second player scored useless goals.

WPA and AGW are not perfect statistics, but they do provide a little more insight in to a player's goal scoring ability.

Monday, July 11, 2011

Answer to my Question via Twitter Posted Earlier

The question I asked earlier today via my twitter @SoccerStatistic was, "Which statistic correlates best with a team's point total?" The options were goals against, corners, goals for, and shots on target. The answer is extremely surprising to say the least.

Another way to ask the question is "Given the goals against, corner, goals for, or shots on targets total for a team in the EPL, which variable would allow you to best predict the point total of the team?" Turns out the answer is not goals for, goals against, or even shots on target. Yep, its the corner total. This means the amount of corners a team accumulates during the season is a better indicator of the team's standing than the other variables. To me, this is mind-boggling. The point of the game is to score more goals than your opponent, yet the amount of corners predict point totals the best.

The way to figure this out is with linear regressions between points and the 4 statistics in questions using season totals for EPL teams. A linear regression tells us how strong the linear relationship between two variables are with a number called the correlation coefficient. A value of 0 would mean there is absolutely no relationship, and a value of 1 would mean a perfect linear relationship. Below is a chart of the 4 variables and their correlation coefficient value. The absolute value of the correlation coefficients are given below, as goals against obviously has a negative relationship with.

Corners just edge out goals for and goals against as the strongest relationship. There is only really one explanation I can think of to explain this: Corners result from pressure on the goal, and more corners would mean more pressure on the goal which corresponds with more wins and a higher point total. Still, the fact that the relationship is stronger than the relationships between points and goals for and points and goals against really amazes me.

A few things to point out: First, the best way to really predict a team's success is with their goal differentials. However, it is still interesting that corners have the strongest relationship of the 4 variables above. Second, the relationship between corners and points shouldn't be read in to too much. This doesn't mean that if a team goes out trying to get more corners they will be more likely to win the game; instead it means that better teams tend to earn more corners based on the way they are playing.

This also leads in to something else I will be working on in the near future which relates somewhat. Are the amount of goals scored by a player a good indication of the quality of the player? Forwards are the highest paid players in soccer, but what if goal scorers are significantly overvalued? Is it right when we say "Player x is a better player than player y because he scored more goals this season"? I think there are a number of ways to test these questions, so check back in the coming week for some results and analysis.

Another way to ask the question is "Given the goals against, corner, goals for, or shots on targets total for a team in the EPL, which variable would allow you to best predict the point total of the team?" Turns out the answer is not goals for, goals against, or even shots on target. Yep, its the corner total. This means the amount of corners a team accumulates during the season is a better indicator of the team's standing than the other variables. To me, this is mind-boggling. The point of the game is to score more goals than your opponent, yet the amount of corners predict point totals the best.

The way to figure this out is with linear regressions between points and the 4 statistics in questions using season totals for EPL teams. A linear regression tells us how strong the linear relationship between two variables are with a number called the correlation coefficient. A value of 0 would mean there is absolutely no relationship, and a value of 1 would mean a perfect linear relationship. Below is a chart of the 4 variables and their correlation coefficient value. The absolute value of the correlation coefficients are given below, as goals against obviously has a negative relationship with.

Corners just edge out goals for and goals against as the strongest relationship. There is only really one explanation I can think of to explain this: Corners result from pressure on the goal, and more corners would mean more pressure on the goal which corresponds with more wins and a higher point total. Still, the fact that the relationship is stronger than the relationships between points and goals for and points and goals against really amazes me.

A few things to point out: First, the best way to really predict a team's success is with their goal differentials. However, it is still interesting that corners have the strongest relationship of the 4 variables above. Second, the relationship between corners and points shouldn't be read in to too much. This doesn't mean that if a team goes out trying to get more corners they will be more likely to win the game; instead it means that better teams tend to earn more corners based on the way they are playing.

This also leads in to something else I will be working on in the near future which relates somewhat. Are the amount of goals scored by a player a good indication of the quality of the player? Forwards are the highest paid players in soccer, but what if goal scorers are significantly overvalued? Is it right when we say "Player x is a better player than player y because he scored more goals this season"? I think there are a number of ways to test these questions, so check back in the coming week for some results and analysis.

Thursday, July 7, 2011

An Analysis of City Pre/Post Abu Dhabi Using the Transfer Price Index

Pretty soon I'm going to start writing the Manchester City statistical blog over at http://www.eplindex.com/ (@EPLIndex). I also just read Pay As You Play by Paul Tomkins. If you haven't read it and you're interested in statistics and football, you should really give it a read. The book basically outlines the trend in the EPL that money buys points using what Tomkins calls the Transfer Price Index. More specifically, the higher the cost of the XI (Tomkins refers to this as £XI) the more a team tends to win. Of course, there are exceptions to this, but in general it seems to hold true. Anyways, when I was reading the book I thought it would be a good idea to analyze City using Tomkin's data, especially when I saw that my future fellow City blogger at EPL Index Danny Pugsley (@danny_pugsley) wrote the "Expert View" for the City section. I'm no expert on the analysis that Tomkins does, but I understand a good amount from reading the book. The subject of the book rings especially true for City considering the recent Abu Dhabi takeover and sudden influx of large amounts of cash for the club.

Some notes before the analysis: One, the data I am using is all from the book Pay As You Play, as I mentioned above. Two, make sure to notice some data is missing for years when City was not in the top flight. Three, the data in the book only goes to the 2009/2010 season, so the 2010/2011 season is missing.

Basically, I looked at 3 questions: 1.) Does City really spend more money since the Abu Dhabi take over? 2.) Does a higher £XI cost equate to success for City in the EPL? 3.) Screw 1 and 2. What if City keeps buying Robinho's?

Does City really spend more money since the Abu Dhabi take over?

Yeah, really dumb question. Pretty obvious the answer is yes. Below is the graph comparing the league average starting eleven cost and the City starting eleven cost since 1992. In the 2008/2009 City's £XI is higher than the league average for the first time since the 1994/1995 season. Remember, Abu Dhabi took over at the start of the 2008/2009 season. For the 2009/2010 season it skyrockets to over £120,000,000. City now has money to spend.

Does a higher £XI equate to success for City in the EPL?

The answer Tomkins gives for EPL clubs in his book is yes. Again, this makes sense. Clubs that are able to spend more on players should be able to produce higher quality sides and win more. I wanted to analyze specifically City's success, so I looked at the data to see if their £XI rank in the EPL follows their league position. In other words, does City succeed more when they spend more? Looking at the graph below, the answer seems to be yes. The league postion (green line) generally follows the club's £XI rank (orange line).

Screw 1 and 2. What if City keeps buying Robinho's?

The first two graphs seem to point to inevitable success for City. They have a lot of money and money can buy success, so they'll succeed, right? People will obviously point to some recent not-so-successful expensive purchases. Robinho, Jo, and Santa Cruz are the 3 big ones. Each has had start percentages of 47, 16, and 16 respectively, despite a massive total cost of £69,000,000. A good graphic to show the efficiency of purchases is the cost per point used in Pay As You Play. Clubs that are efficient in this regard will have spent less money per point earned, while clubs that are inefficient will do the opposite. The graph shows how much City spent in each year for each point they earned. Not surprisingly, the cost per point has spiked since 2008. This may seem like money is being wasted. While City may not be getting as much bang for their buck, it likely won't matter in terms of success. According to Tomkins, the highest cost per point goes to Chelsea in 2006/2007. They finished in 2nd that year. It seems that simply having a lot of money can trump inefficiencies displayed from the cost per point value. Tomkins even refers to City's high cost per point on page 18: "Manchester City will certainly close the gap for this unwanted honour (although if they win the league, they won't care what people think; they could probably afford to pay £4m or £5m per point if it would guarantee them success)." So yes, City may make some poor purchases like Robinho, Jo, and Santa Cruz in the future. All in all, it doesn't matter that much though. City has so much money that they'll win anyways.

Wednesday, July 6, 2011

Fun With Graphs

Often graphs can tell us a lot more about certain data then just the numbers itself. At least they are usually easier to understand. I just downloaded Aaron Nielsen's (@ENBSports) amazing database from the 2010 MLS season and started playing around with it. Here are some interesting graphs I came up with:

Another graph that highlights domination (in this case probably in a negative sense) of one team over all the others. All teams fall in the range of 1.4 to 1.8 cards per game. However, its clear that Toronto is an outlier with 2.17 cards per game.

This is probably a graph that already exists somewhere, but I made it anyways. It really highlights how much Seattle dominates attendance in the MLS. Also added in a bar for average attendance (between Chicago and Salt Lake) for comparison.

Another graph that highlights domination (in this case probably in a negative sense) of one team over all the others. All teams fall in the range of 1.4 to 1.8 cards per game. However, its clear that Toronto is an outlier with 2.17 cards per game.

This graph once again shows domination by one team in a certain statistic. Dallas scored almost 20% of their goals from PK's. That's 1 out of every 5 goals. This almost doubled every other team in the MLS last season, and was 10 times the percentage of Seattle. Hmm. Not exactly sure what the explanation here is. Is Dallas really good at diving? Are they being favored by refs? Are they just getting a lot of chances in the box? Something to look at in the future.

For the percentage of goals scored outside the 18, I took the 2 lowest, 2 highest, and the average. Dallas (likely from their massive share of goals from PK's) and Columbus have the lowest percentage of goals scored from outside the 18. New England and Chivas USA have the two highest percentage of goals scored from outside the 18. This shows not every team is scoring goals the same way in the MLS. Having a high percentage of goals from outside the 18 doesn't exactly mean the team is being creative or is better at long distance shooting. Instead, it more likely tells us that the team struggled in scoring goals within the 18, where the bulk of goals are scored. Dallas and Columbus were 4th and 5th last year, respectively, while New England and Chivas USA were 13th and 15th, respectively.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)